Buy Buy Baby Robbery Downers Grove Il Car Seat Stolen

The Serial Killer and the 'Less Dead'

The only reporter who's talked to Samuel Little tells how he was caught — and why he almost got away.

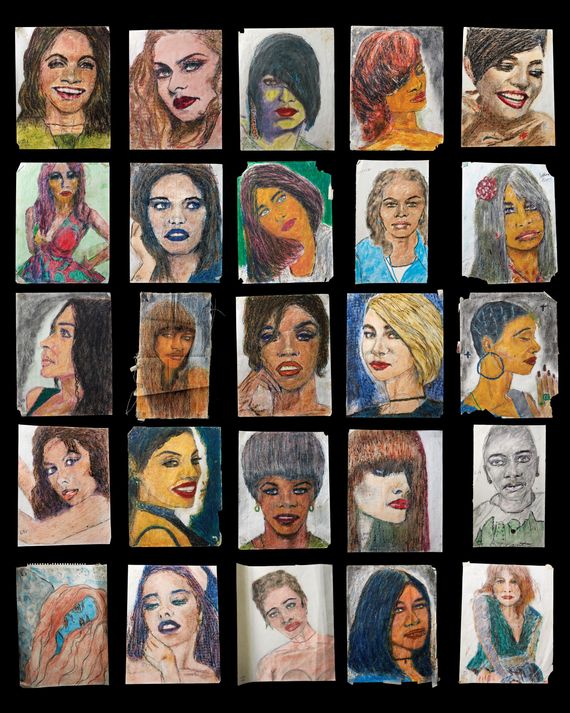

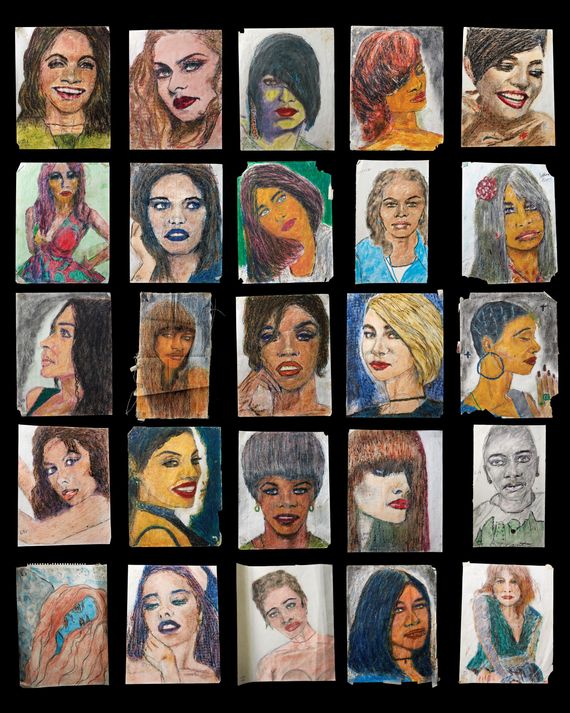

Little's drawings of his victims, made in prison. Illustration: Samuel Little

Little's drawings of his victims, made in prison. Illustration: Samuel Little

Little's drawings of his victims, made in prison. Illustration: Samuel Little

California State Prison, Los Angeles County, is located roughly 70 miles northeast of the palm tree-lined boulevards of Beverly Hills, but it may as well be 70 million. The prison is an ecosystem unto itself, where more than 3,000 men live sandwiched between the sunbaked terrain and a wide, unforgiving sky. In the middle of a summer day, when temperatures regularly reach 105 degrees in the shade, and the desert wind blows so hot it feels like it could sear the eyebrows off your face, the landscape conveys an almost biblical feeling of punishment.

On the morning of August 18, 2018, after waiting seven hours for my number to come up, I faced the prison's iron security gates, but I kept setting off the metal detector. I wound up having to pry the underwire out of my bra with my teeth because there were no sharp objects available. "Gnaw that shit out," said one of the other visitors watching me in the bathroom. "You got this."

Nearly ten months before, I'd interviewed LAPD Homicide detective Mitzi Roberts — the model for the Michael Connelly character Renée Ballard — and asked her what case she'd been most proud of in her career. "I'm proud of them all," she said, "but I did catch a serial killer named Sam Little once. That was pretty cool."

I'd gone home and learned that Samuel Little, a.k.a. Samuel McDowell, had been convicted in Los Angeles in 2014 for strangling three women to death in the late 1980s. Roberts told me she suspected him of many more killings across the country, and after she got him, she figured other police departments would start connecting him to their own unsolved murders. To her frustration, that never happened. She thought maybe it was because Little preyed on the "less dead," people who live on the margins of society and whose murders have historically tended to be not as thoroughly investigated as those of their wealthier, whiter, and perhaps more sober counterparts. Roberts had recently heard through the grapevine that Little, who was 78, was in poor health. "Who knows how many families will never know what happened," she told me.

For reasons part professional and part personal — I'd had my own run-ins with drugs and violent men and felt lucky to have gotten away relatively unscathed — I decided I'd try to get Little talking. Unbeknownst to me, a Texas Ranger named James Holland, who was passionate about cold cases and had caught wind of this evasive drifter's suspected killings, was also plotting to get Little to confess. The two of us would end up converging on him just a few months apart.

While waiting for a visitor clearance, I exchanged letters with Little, throughout which he staunchly maintained his innocence. That first day I went to see him, I brought only a clear plastic bag full of quarters, per prison rules, which I used to buy him Funyuns and a package of Little Debbie Honey Buns. I put them on the table between us as I sat down.

"Hello, Sam," I said.

Little was wheelchair-bound, suffering from diabetes and a heart condition. He wore standard prison-issue shapeless denim pants, a blue T-shirt with CDC printed on the back, and a pair of white orthopedic sneakers due to a toe amputation. The tail end of a baby-pink heart-surgery scar the size of an earthworm peeked out from the top of his tee. He had a thinning pelt of white hair and a beard to match. Age spots discolored his skin, giving him the appearance of a molting lizard. But I could see the evidence of the man he once had been: a six-foot-three powerhouse with catcher's mitts for hands. I could still make out the strong cheekbones, pale-blue-green eyes, and handsome face that might once have put his victims at ease. The sound of children, chatter, and vending machines bounced off the room's cinder-block walls. Little wagged a finger at me.

"You!" he said. "You're my angel come to visit me from Heaven. God knew I was lonely and he sent me you. You want a story?Oooooeeeee, do I have stories."

He spoke in a soft, cryptic patois, a mash-up from his origins in Georgia and his years growing up in the Ohio steel town of Lorain. To understand him, I had to lean in and then lean in again, until I was approximately a foot from his face.

We talked that first day about our childhoods, about my kids, about his family tree, which he claimed includes Malcolm X. We talked about his teenage mother abandoning him as an infant by the side of a dirt road. We talked about his late long-term girlfriend, Jean, who'd been a master shoplifter and supported them that way for years. We talked about how he liked to travel. We talked about his art. He had learned to draw during his first prison stay — three years for robbing a furniture store in Ohio in his 20s — and it was still his preferred pastime.

"What do you like to draw?" I asked.

"Oh, girls. I mean women. I mean ladies," he said, seeming to search for the term I'd find least offensive. I wondered if the real answer was "victims." "I can draw anything. Paint, pencil, whatever I can get. I can do all the light and dark. Just like I see you right now."

Little studied me, and I felt acutely self-conscious. What was he seeing? What had he seen in them? How do you find someone simultaneously worthy of the kind of deep attention it takes to draw them and also so completely expendable.

"I live in my mind now. With my babies. In my drawings," he said. "The only things I was ever good at was drawing and fighting."

We discussed his hero Sugar Ray Robinson and the prizefighting career Little almost had; he was a light heavyweight who'd been called "mad" for his speed and fury. The Mad Daddy. The Mad Machine. The Machine Gun. I sat with him for hours that day and returned the next.

After about six hours total of talking, he lingered on a story about a woman he'd once known in Florida, then his eyes turned opaque. He veered off the subject, as he was wont to do.

"I want a TV," he said.

"Okay. I want things too," I replied.

He gazed at me with a flat, reptilian expression. It was a side of him I hadn't seen. I instinctively shifted back in my seat.

"You going to buy me that TV?"

"I don't know, Sam. Am I?"

He laughed and drummed his half-inch-long dirty fingernails on the table. "Okay, okay. You got me! What do you want to hear about for your story, Little Miss? You want to hear about the first one?"

I dug my toes into my shoes — was this really going to happen? It was.

"She was a big ol' blonde," Little said. "Round about turn of the New Year, 1969 to 1970. Miami. Coconut Grove. She was a ho." Then he corrected himself: "A prostitute. She was sitting at a restaurant booth, red leather, real nice. She crossed them big legs in her fishnet stockings and touched her neck. It was my sign. From God."

And with that, he began to tell me about the women he'd killed. He thought he remembered 88, give or take a few, he said. He told me about a couple dozen of them in astonishing detail as, over the next month and change, I sat with him for hours every weekend while he took me back through his past — when the road was his home, and the back alleys and underbelly bars of cities across the country offered a feast of low-hanging fruit, women whose eyes were half-dead already. Women who Little believed had only been waiting for him to show up and finish the job. He imagined himself as some sort of angel of mercy, divinely commissioned to euthanize. At least sometimes he did. Other times, he told me, he believed he was the devil.

A self-portrait of Little. Illustration: Samuel Little

The outskirts of Odessa, Texas, don't look that different today than they did 25 years ago, when Little killed Denise Brothers — one of the women whose murders he described to me and whose story I decided to investigate myself. The town is surrounded by a dust-caked moonscape studded with oil derricks and drilling rigs. At night, the oil fields appear to be lit from within, casting an unearthly glow into the dark expanse of West Texas sky.

Follow the railroad tracks into Odessa proper and you pass megachurch after megamall after megachurch before reaching rows of modest, well-tended brick houses familiar to any watcher ofFriday Night Lights,the show famously based on the town's high-school football team.

These houses include the one in which Brothers, who was born in 1956, grew up.

When she was killed, at age 38, Brothers didn't live in her childhood home anymore, but her middle two boys, 9-year-old Dustin and 14-year-old Damien, resided there with her parents. Her oldest, Dennis, had long since moved to Miami, and by the time her youngest, Derreck, was born, she was too far gone on heroin to parent him and he'd been placed for adoption.

On the night Denise died, Dustin and Damien were probably tucked into their beds. As Damien told me when I visited him in Odessa this summer, he would often read a comic book under the covers with a flashlight, waiting up, listening to see if his mother was going to try to break in again like she did on Christmas, stealing whatever presents she could carry. He wanted to catch her in the act, he said. Or maybe he just wanted to see her face.

Damien knew she felt guilty, he said, because she'd told him over and over. It didn't stop her from doing it again.

"You get hungry enough, baby, and you do what you need to do. As long as there's a tomorrow, there's always another chance. I'll get back those gifts," she'd assured him. She usually did get the gifts back. And they usually forgave her, especially Dustin, whose life would spiral downward after the loss of his mother. He was shot to death outside a strip club at age 21 by a still-unknown assailant.

Just a few days before Denise's murder, the boys had ridden their bikes through the rain to visit her. She held their wet faces in her hands and kissed their cheeks, but they could tell they'd arrived when a mean jones was setting in. They were intimately aware of her addiction, having numerous times witnessed her stabbing herself with a needle, searching for a vein. She sent them out for a loaf of bread and a pack of cigarettes.

"You're supposed to take care of us, you know, not the other way around," Damien told her before they left, his arm protectively around his little brother. When the boys returned from their errand, the door was locked and nobody answered their knocks.

Flipping through a stack of Polaroids on Damien's kitchen table, I could see that, in her day, Denise had been a head-turner. Based on her report cards, her school performance was spotty, but she'd had the talent of simply being herself: fashionable, creative. She'd made her own too-short dresses that she paired with matching go-go boots and blue-glitter eye shadow she'd shoplifted from the pharmacy.

Denise got married at 15 to a man both violent and vain, at least judging from the tales her children later heard about him. She was stumbling out of that marriage when her second husband, Ron, caught her. Ron was square jawed and broad shouldered, with a theatrical mustache and a defiant glint in his eye. He'd been a roofer, and from the outside, with their well-kept home and two beautiful little boys, it seemed as though all was well — until the day Denise found him shooting up in the bathroom. She packed a bag and walked out the door, but she returned and eventually developed her own addiction. There were two more husbands and what probably felt like a lifetime between first getting hooked on heroin and stepping out into that cold, clear January night.

A sliver of moon hung over the sad industrial stretch she was about to stroll. The motel where Denise stayed was a shithole, according to Damien, but he also said his mom was scrupulous about keeping her room clean and tidy. At some point before she went out that night, she buttoned the waistband of her newly shoplifted Gitano jeans, maybe ran her hands over her sharp hip bones. She pulled a BedazzledD T-shirt over her head.D for Dennis, Damien, Dustin, Derreck.D for Denise. She was headed to see her pimp, who stayed at an even crappier motel nearby.

From what Little told me, Denise made it only half a block before he approached her in his boxy white Cadillac with the blue fabric top. The car idled. Hunched and shivering inside her down coat, she gestured for him to pull over.

He slouched in his seat, partially in shadow. I imagine a tiny flicker of misgiving fluttered in Denise's gut, that she paused for a moment before she yanked open the passenger-side door. But there's no way to know what she felt or thought that night, because she is no longer here to speak for herself. All I know is from the coroner's report, detective interviews, and what Little recounted to me.

In short, he said he bought a bunch of crack and black-tar heroin for Denise and her pimp, who'd joined them to get high. Afterward, the pimp cheerfully patted Denise on the ass and left her with Little to pay the bill in trade.

Little is a talented storyteller, his tales imbued with rich detail. Every time he began to tell me about another murder, I found myself illogically hoping that maybe this one would have a different ending. Maybe this victim would be the one who got away. But I already knew the ending to Denise's story. I had visited her grave and that of Dustin, buried close by.

"What did you say to her?" I asked.

"I told her I was an artist. She was a spicy one. I told her I could draw her so pretty, like van Gogh!" He cracked himself up with that one. "I told her she was beautiful. I said, 'I love you.' "

He told them all he loved them, he said. I wonder how it sounded to them, coming from this trick they'd just met. Maybe it had sounded strange and sad but also sort of sweet. Or maybe they just wanted him to shut up and get it over with already.

He then pulled into an alley, he said, and as she prepared to give him a blow job, he grabbed her by the throat and tossed her over the back seat like a doll, where he strangled her with one hand while masturbating with the other. When she fought, he fought back harder.

Because killing was synonymous with sex for him, Little said he made the encounters as "long and slow as possible," often letting his victims repeatedly regain consciousness. The last time Denise came to, her head was in his lap, her eyes "big as marbles."

"Big as your eyes are right now," he said to me, smiling. "I told her, 'I own you. You're mine forever.' "

She cried, and he kissed the tears from her face. Then he squeezed the life from her.

"Why do you feel you need to own women?" I asked.

"I wanted their helplessness. All I ever wanted was for them to cry in my arms."

"Denise cried," I said. "If it was all you wanted, why didn't you let her live?"

"Well, you got me there," he said. "Maybe it wasn't all I wanted."

Denise Brothers, shown at left at age 15, was killed by Little in 1994, when she was 38.

Three weeks later, when Detective Sergeant Snow Robertson arrived at a vacant lot at 2700 Van Street, Denise was lying half on her side, face to the sky, arm wedged under her at an odd angle. A truck driver had found her body and called the police. Though her skin had begun to slip from its contours, Robertson still recognized her. Denise was familiar to local law enforcement.

The medical examiners pulled in behind him, but when they approached, he held out a hand to stop them. While many detectives aren't eager to investigate the often hard-to-solve cases of the less dead, Robertson was the exception. He told me he'd wanted to make sure Denise was done right, so he walked the scene himself, photographing what needed to be photographed, tagging the evidence. He bagged her hands, zipped her into a black body bag, lifted her up and placed her gently into the back of the coroner's van.

From vaginal swabs, Denise's pimp and another man were identified as suspects in her murder, but both men denied it and Robertson believed them. Yes, they were both complete scumbags, but Robertson's intuition told him someone far more nefarious had killed Denise. So the detective sergeant put his back into it. He called in the Texas Rangers, an assisting organization with extensive investigative resources and multi-jurisdictional capability. He questioned every single prostitute brought in on other charges to see if they had heard anything. He sniffed out Denise's associates and hit only wall after wall.

Not long after Robertson got Denise's case, he arrived home an hour and a half late and dove for the phone to call his 9-year-old son, who lived with his former wife. It rang and rang. No luck. These homicides always made him desperate for the sound of his son's voice. He tossed his briefcase under the desk off the kitchen that served as an office in his two-bedroom apartment, and he settled in.

A couple of nights a week, Robertson generally spent a few hours filling out forms on his homicide cases past and present and mailing them to ViCAP — the Violent Criminal Apprehension Program — which is both an FBI unit and an information-sharing database, begun in 1985. The database enables local cops like him to enter detailed findings about violent crimes that can then be compared with other cases nationwide. ViCAP works in tandem with local and federal DNA databases, but, while widely celebrated for solving numerous crimes over the past decade, DNA alone isn't of much use in many cold cases, which number up to 240,000 in the United States since 1980. Physical evidence either never existed in these older cases or has been degraded or destroyed. ViCAP facilitates more traditional investigations. The rub is that entering a case into the system is voluntary. A pattern can't be detected if police officers don't take it upon themselves to commit a case to ViCAP.

But Robertson believed in its still-underused and underrecognized capabilities. He imagined a U.S. law-enforcement system that was more than a scattered network of haphazardly connected jurisdictions and instead a single organism working toward a common purpose: getting the bad guys.

He pulled out a ViCAP booklet and began to fill in the information he'd collected about his latest case:

Date: February 2, 1994

Agency: Odessa Police Department

Victim: Denise Christie Brothers

Case Type: Homicide

Offender: Unknown

Someone in the future will see the pattern,Robertson thought.Someone will find the missing piece.

Little after attending a pretrial hearing in late November in Odessa, Texas. Photo: Mark Rogers/Odessa American via AP

During my visits with Little, I got used to waking up at four in the morning on weekends and driving the hour and a half to the prison while the dusty-rose dawn broke over the desert. I got him a Coke and some Lay's potato chips from the vending machines, and we chatted.

He told me that no one could understand how much love was in his heart for the women he killed, his "babies." Even though he said he felt bad about the pain he put his victims through, thinking about them was the only thing that made him feel alive in his dank cave. So day after day, he lay alone and replayed the killings, drawing his babies from memory when he could get his hands on a pencil.

"How did it feel to kill them?" I asked.

"Oooeee, it felt like heaven. Felt like being in bed with MarilynMon-roe!"

Marilyn Monroe. A cartoon woman. I didn't point out to Little that in bed wasn't where he ever wanted to be with women, despite his insistence on how he loved women, worshipped them even. He said when he was a child he didn't realize they were humans who ate and slept and shat. He thought they were angels.

"You wouldn't be the first man to be disappointed by the humanity of women," I said.

"That's my smart baby," he said, tapping two fingers to his temple. "You got the psychology."

When he talked about the murders, he lit up like a kid on Christmas morning, becoming animated and performing an elaborate pantomime. He hugged himself and made kissing noises. With one outstretched arm, he demonstrated just how much force it took to crack a hyoid bone.

"I had my own hard days, you know," I told him. "I'm glad I never met up with someone like you one dark night."

"But I never killed nobody like my smart baby here," he protested. "I never killed no senators or governors or fancy New York journalists. Nothing like that. I killed you, it'd be all over the news the next day. I stayed in the ghettos."

"How did it feel to finally get caught?" I asked.

He went into what was a standard rant about being set up by the LAPD. He still hadn't confessed to me about the L.A. murders.

"But you did kill those women?"

"You think you know me? You think you in here sparring with Mr. Sam, now?"

He laughed and shadowboxed, throwing mock punches an inch from my cheekbone. He liked to scare me a little when I stepped out of line, reminding me that he was in control of the conversation. I flinched and flinched again.

"I like to think we know each other a little by now," I managed to say. "And yes, I think you killed them."

"Well, you're right about that, Lil' Miss," he said. "But they still set me up."

"What do you feel you deserve?" I asked.

"What's that question?"

"We live in a society that has rules. And one of those rules is that you don't go around killing people for fun. So what I want to know is, what do you think you deserve for what you did?"

It was the wrong question. I'd moved too quickly. He slipped into some other world; when he looked back at me, it was with utter blankness.

Los Angeles detective Mitzi Roberts began to put together the puzzle of Sam Little in 2012, 18 years after her Odessa colleague had entered the information about Denise Brothers into ViCAP, though Roberts was still unaware of the connection. Working under a grant from the National Institute of Justice, the LAPD had instituted the Cold Case Special Section, tasked with screening DNA evidence from cases long since considered lost causes.

Los Angeles had thousands of cold-case homicides lining its shelves, many of them committed during the 1980s and 1990s in and around South Central. Ravaged by the crack epidemic and the Reagan administration's subsequent War on Drugs, South Central became a playground for predators. During that era, up to seven sexually motivated serial killers — including Lonnie Franklin, Chester Turner, Michael Hughes, Richard Ramirez, Louis Crane, and Samuel Little himself — operated with near impunity in the area, according to local law enforcement and community activists.

One morning in April 2012, a ripple of excitement moved through the hallways of headquarters. Of the hundreds of cases screened through the federal database, there had been a case-to-case DNA match: Genetic information connected the murders of Audrey Nelson in August 1989 and Guadalupe Apodaca a month later to a man named Samuel Little, whose DNA had been retrieved in the mid-1980s when he'd pleaded guilty to assault in San Diego.

Little had left DNA fingerprints when he ejaculated on Apodaca's shirt and when Nelson fought for her life and secured his skin cells under her nails. With these matches, the chances that the genetic material could belong to someone other than Little were one in 450 quintillion in the U.S. African-American population. Still, it was only a start. A match indicates that the suspect was with the victim at some point, but it often isn't enough to arrest anybody, especially if, like these women, the victims were prostitutes with multiple DNA profiles present on their bodies.

Roberts and her partner, Rodrigo Amador, were assigned to the case. A veteran homicide detective with intelligent brown eyes and legendary tenacity, Roberts was confident that Little was her guy. What she didn't know yet was how to prove it. And what she really didn't know was where to find him.

Roberts pulled toward her the first of two stuffed four-inch binders, case files commonly referred to as "murder books." "Opening a cold case is like opening a good book," Roberts told me. "The story is in there somewhere, if you know how to work backwards from the end."

That day, she learned that Apodaca's story ended in an abandoned garage in South Central Los Angeles. A 9-year-old boy kicking a soccer ball against the wall of the building had peeked into one of its glassless windows and spied a naked pair of women's legs. When the patrol unit showed up, they found 46-year-old Apodaca wearing only a half-torn buttercup-yellow men's shirt, one tarnished silver earring, and, on her middle finger, a silver ring set with a large square of turquoise. When the coroner's investigator turned her over, the curtain of dark hair that had been obscuring her face fell back, revealing white roots. Apodaca was no longer young, and she had a look about her of someone who might never have been.

Roberts studied the map in the binder and thought about how, 15 years earlier and right around the corner from where Apodaca was found, the kidnappers of the young white heiress Patty Hearst had been gunned down in front of the hungry eyes of an entire nation. Apodaca's killer had slipped off into the night, in front of the eyes of nobody.

It was hours before Roberts pulled the second book toward her to meet Audrey Nelson, born August 27, 1953. The high-school photo of a pretty if somewhat bewildered-looking blonde was unrecognizable as the emaciated, broken body wearing only a red sweatshirt when she was found curled into a fetal position in a dumpster behind a Chinese restaurant. On the knuckles of her left fist were stamped the letters T-R-U-E. The next angle revealed their counterpart, L-O-V-E. Nelson's body was a road map of beatings, burns, and stark black tattoos: a tarantula on the side of her neck, a heart on her breastbone, and a cryptic symbol with an arrow at its center on her hand.An arrow pointing to Sam Little, Roberts thought.

She and Amador began working up a dossier on him, aliases Samuel McDaniel, Samuel McDowell, Willie May Clifton, and Willie Lewis. The detectives ran rap sheets and arrest records, pulled prison packages, did vehicle searches. When the results began to pile up on her desk, Roberts's unflappable cool gave way to astonishment, even anger. The question wasn't where he'd been hiding all these years. He hadn't been hiding — he had been committing crime after crime in plain sight.

Little's arrest history begins in 1956 with the theft of a bicycle, for which he was sent to the brutal Boys' Industrial School in Lancaster, Ohio. Over the next six decades, he was repeatedly arrested in Ohio, Maryland, Florida, Maine, Connecticut, Oregon, Colorado, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Arizona, Georgia, Illinois, Missouri, California … the list goes on. Charges include burglary, breaking and entering, assault and battery, assault with the intent to rob, assault with a firearm, armed robbery, assault on a police officer, solicitation of prostitution, DUI, shoplifting, theft, grand theft, possession of marijuana, unlawful flight to avoid prosecution, resisting arrest, battery, false imprisonment, assault with great bodily injury, robbery, rape, and sodomy.

Roberts did the math. For all of this, he'd served just ten years altogether. Where could she even begin? She decided to start by examining the most violent crimes in his voluminous record.

In September 1976, Little was arrested in Sunset Hills, Missouri, for the rape, assault with great bodily injury, and robbery of Pamela K. Smith. She'd shown up hysterical on a stranger's doorstep after escaping Little's car and running nearly naked through the night, her hands bound behind her with cloth and electrical cord. Little had strangled, bitten, beaten, and sodomized her. He was convicted of the lesser charge of assault with attempt to ravish and served three months.

Roberts had to read that twice: threemonths for assault and rape. He'd done threeyears for robbing a furniture store. And what the hell was "attempt to ravish," anyway? It sounded like something out of a romance novel, not a police report.

She went on. In September 1982, the nude, strangled body of 26-year-old Patricia Mount was found in Alachua County, Florida. Witnesses identified Little as the man last seen leaving with Mount in his brown Pinto station wagon. Hairs found on the victim were similar to Little's. He was tried for the crimes, but due to a lack of definitive physical evidence, the jury acquitted.

The following month, the remains of 22-year-old Melinda LaPree were found by a groundskeeper in a cemetery near the small Gulf town of Pascagoula, Mississippi, three weeks after her boyfriend had reported her missing. A disarticulated hyoid bone and fractured cricoid cartilage indicated strangulation. Witnesses identified Little as the man with whom LaPree had been seen getting into a brown Pinto station wagon. Two prostitutes interviewed during the investigation, Hilda Nelson and Leila McClain, revealed that Little had assaulted and strangled each of them, though only Nelson had reported the crime; each provided eyewitness identification. Little was arrested for LaPree's murder, but the charges were ultimately dismissed owing to lack of physical evidence and a vague rumor of witness tampering.

In October 1984, Little was caught by San Diego patrol officers in the act of beating and strangling Tonya Jackson in the back seat of his black Thunderbird. He was charged with rape and assault with great bodily injury. The San Diego police connected him to a September 1984 attack on Laurie Barros, who had lived to tell the tale by playing dead after being strangled and left by the side of the road. The cases were tried together, with added charges of false imprisonment. Little pleaded guilty to two counts of assault with great bodily injury and one of false imprisonment. He received a four-year prison sentence and served only a year and a half before being paroled, in February 1987, after which he traveled 125 miles north to his old stomping grounds of Los Angeles. There, he shacked back up with his long-term girlfriend and continued his rampage of theft by day, murder by night.

Over and over they had him,Roberts thought.How could this have happened? How it happened was that a judge in Missouri thought three months was an appropriate sentence for rape and assault. How it happened was that he chose to dispose of victims society already considered trash.

Roberts spent her days with a phone glued to her ear, talking to investigators in Florida, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Oregon, and Texas. This guy was slippery as a greased pig. He had no address, no registered car, no credit card. Her sense of urgency grew daily as she pushed against her lieutenant's threat to release a wanted flyer. She worried Little would see it and disappear forever.

She located an outstanding 2007 narcotics warrant, and the DA agreed to extradite Little if Roberts could only find him. Finally, Robbery-Homicide Division detectives turned up a lead, a prepaid Walmart card on which Little's Social Security payments were being deposited. It had last been used in Louisville, Kentucky. The U.S. Marshals Fugitive Task Force jumped in, locating Little at Wayside Christian Mission in Louisville and arresting him on the minor drug charge. He was extradited and sat in a California jail, refusing to talk, probably confident of being freed yet again.

They had him, but could they keep him?

Roberts entered her cases into the ViCAP system, which now had far more sophisticated technology than when Detective Sergeant Robertson had used it years earlier. She thought — she knew—there were more. Where were they?

In late November, seven months after her pursuit of Little had begun, Roberts got what she needed: another DNA hit. Little's genetic material had been detected on the bra and fingernail kit of 41-year-old Carol Alford, who'd been found strangled in a residential South Central alleyway in July 1987. It was the tipping point. In January 2013, Assistant District Attorney Beth Silverman filed three charges of murder against Samuel Little.

Roberts and her new partner, Rick Jackson, traveled to Pascagoula to talk to a pair of Little's living victims, former prostitutes Nelson and McClain, and perhaps persuade them to come to L.A. to testify. The two black women were skeptical — nothing had happened the last time they told white cops about what Little had done to them — but they eventually began to take Roberts, Jackson, and a local police officer named Darren Versiga back to 1982, when they'd lived and worked in a now-razed area of town called Carver Village. Located directly across the street from the projects, it was known as the Front — McClain described it as a "small California." If you wanted it, you could find it in Carver Village: booze, girls, uppers and downers called T's and blues, guns, dope, and boosted goods sold cheap. It was a world under a bell jar, a world so ignored by law enforcement that the prostitutes who prowled the neighborhood had a pact to check on each other if anyone went missing for too long. This pact had saved Nelson. Her best friend had knocked on the door to Nelson's apartment, and when that didn't produce an answer, she had come around and screamed through the window, and Little had run.

Next, McClain told them a by-then-familiar story about a man approaching her on the street, offering her $50 for a date, and charming her into his car. "The way he came around with that hand.Pop!Pops you in the head somewhere right there that just — it will either wake you up or knock you out," she said. "I woke up." She scrapped with him so fiercely she managed to break from his grasp and run half-naked across four lanes of heavy traffic.

Nelson had reported her assault with no result; McClain hadn't even bothered until she was approached by detectives during the LaPree investigation. When Roberts asked why she hadn't gone to police, McClain replied, "Ain't nobody cared until that white girl turned up dead a year later.

Didn't nobody care about a black prostitute in Mississippi. No, ma'am, they didn't."

Sergeant Versiga, who had arranged the interview, seconded McClain: "It wasn't really possible to commit a crime against a black prostitute. It just wasn't a crime."

Despite the two women's ambivalence and the layers of armor they'd built up over years of being demeaned and dismissed by law enforcement, they agreed to testify at Little's trial.

Months later, when McClain entered the courtroom to face her attacker, she was visibly shaking. She wore a pink suit and seemed to be shrinking into it with every step. Halfway to the witness stand, she sank to the polished hardwood floor, sobbing. Nelson and Versiga lifted her by the elbows and led her out.

In the hallway, Nelson — who'd known McClain for 30 years, ever since she'd sold her a pair of patent-leather pumps from the trunk of her car — held her friend upright. "Look at me," Nelson said. "You don't gotta be scared of him anymore. I know we didn't come this far for you to fall apart now."

"I'm not scared," she said, meeting her friend's eyes. "I want to kill him. I want to kill that motherfucker."

"You don't gotta do that," said Versiga. "You just go in there and tell the truth."

With that, all five feet three inches of McClain reapplied her lipstick, squared her shoulders, and headed back in.

On September 2, 2014, after weeks of testimony from criminalists, expert witnesses, pathologists, police officers, and living victims, plus an inspired closing argument by Silverman, a jury of Little's peers convicted him of three counts of first-degree murder, for which he was sentenced to three consecutive life sentences. Roberts picked a red M&M out of the bowl in front of her at the prosecutor's table and winked at Little.

He glanced at his public defender, Mike Pentz, who'd entreated him the whole time not to engage, not to stare at Prosecutor Silverman's ass, not to go off on a rant. Fuck it now, Little thought. But he told me later that all he could think to do in that moment was wave good-bye to Roberts. So he did. Then he raised an impotent fist in protest as he was wheeled from the courtroom.

The next time Little faced Roberts, it was early this fall, through a camera in the Wise County sheriff's office in Decatur, Texas, about 70 miles northwest of Dallas, where red-tailed hawks make lazy circles over rolling fields dotted with cattle. In May, three months before I first visited Little, Texas Ranger James Holland had gotten him to officially admit to the murder of Denise Brothers. Eliciting confessions from serial killers is an unexpected specialty for this affable six-foot-three guy wearing a tall hat and silver badge and sporting a 1911 ivory-handled pistol on his double-rig belt — "Some kind of cowboy from Mars," as Little described him to me.

Holland had heard about Little after speaking at a homicide-investigation conference this past February, when a Florida cold-case detective approached him with suspicions about a murder in his jurisdiction. Holland's interest was piqued, but he needed a Texas case to get involved. He reached out to FBI ViCAP crime analyst Christie Palazzolo and Department of Justice ViCAP liaison Angela Williamson, both of whom enthusiastically leaped into the investigation, locating not one but three possible Texas murders, including Brothers's. The information Detective Robertson had painstakingly entered 24 years earlier finally surfaced.

To get the Brothers confession from the guy L.A. cops called the Choke-and-Stroke Killer, Holland played on the fact that Roberts was the person Little most loved to hate. "What can I tell you about Sam?" she'd told Holland the day before this first visit. "He loves peanut M&M's, he hates women, and he really fucking hates me. Oh yeah, and don't call him a rapist. He's way more sensitive about that than being a killer."

Holland had begun with the familiar routine of establishing a rapport: in-jokes and nicknames, ribald profanity, heartfelt revelations on both sides. Above all, hovering between them was Holland's suggestion that secrets are fun but they're even more fun to share.

They agreed to be "Sammy" and "Jimmy," even though Little insisted no one had called him Sammy but his immediate family; Holland assured him no man had called him Jimmy, ever.

In exchange for the initial confession, Holland had agreed to move Little away from Roberts and the prison in the middle of the infernal desert to a facility in Texas, where they might share some local barbecue and a chocolate milkshake. He promised to fly him in the Rangers' fancy private jet — an adventure. And as part of the deal, Little had vowed that he would continue to admit to murders across the country.

And now, on a late-September morning, that was about to begin: Gathered around a shaky video feed in a room adjacent to the one where Jimmy sat across from Sammy, were Roberts, her partner Tim Marcia, L.A. prosecutor Silverman, and ViCAP specialists Palazzolo and Williamson.

Little knew he had an audience. Everyone he'd ever met had seemed to him like an actor in the personal movie of his life. But what's the point of a movie no one ever gets to see? Now the moment had arrived … but wait. As Little told me later, if Jimmy and Roberts really thought he was going to give up his secrets for a lousy milkshake and a plane ride, they had another thing coming.

Little turned to face the camera positioned in the upper corner of the room. Spittle gathered in the corners of his mouth, and he pounded a fist on the table. He reared up and spat, the top half of his body seeming to inflate like some shadow-world version of the Incredible Hulk.

"Those dogs. I ain't saying shit. This is bullshit. I ain't telling you fucking nothing. Those lying bastards. Fucking cops. They think I did it, so they set me up. They know I did it, so they set me up. It was the Mexican Mafia killed that bitch — I can't even pronounce her name."

Roberts watched, stone-faced.There you are again, old buddy,she thought.I almost missed you, you fuck.

I'd seen this terrifying rage rise in Little only once. He was telling me about a little girl with red ringlets in his third-grade class who had stared at him with wide green eyes and touched her neck. Not even he knew it yet, but somehow she sensed it was his weakness and she'd taunted him.

"Must have made you angry," I said.

"No, no," he replied in his genial way. "I don't get angry at girls. Unless they have a very poor disposition."

"What do you get angry at, then?"

"Bullies," he said, his eyes turning to cartoon pinwheels. "Men." He leaned forward, digging his nails into the table, his voice dropping to a growl. My eyes sought the guard, calculating the distance between us, estimating how long it would take him to reach me.

When Little went dark in the Wise County interview room, Holland shifted just slightly in his chair so the handle of his pistol was a few inches farther from the reach of this man who had turned on a dime from courteous to menacing. Holland wasn't so much worried about his safety, but he certainly had an icy jolt of panic that he might be about to preside over the biggest near-miss serial-killer case of all time.

But Jimmy brought his friend Sammy back, talking about girls, kids, and football, employing a more professional version of the approach I'd stumbled upon: giving Little a window with a view into what it might be like to feel fully human. Sammy calmed. He began to confess.

Soon after, Holland started contacting law-enforcement officials from dozens of far-flung jurisdictions, from California and New Mexico to South Carolina and Kentucky, capitalizing on the work of Palazzolo and Williamson. When Little would say he'd killed a woman in Arizona, for example, the pair would scour databases and reach out to police in the county or city where a murder seemed to match his description. Holland would then summon them to Decatur to sit with him and interview Little, who sometimes drew his victims as he detailed their demises.

So far he has described 93 killings, 39 of which have been confirmed by the available evidence — like those of Rosie Hill, killed in 1982 in Marion County, Florida; Daisy McGuire, killed in 1996 in Houma, Louisiana; Nancy Carol Stevens, killed in 2005 near Tupelo, Mississippi. Little's first murder — the first one he told me about, of the blonde woman in Miami — was recently confirmed, but her name hasn't yet been released.

The day I drove to Wise County from the Dallas airport in October, a freezing rain turned the world around me into a white screen. I'd come here for what I suspected would be my last visit with Little.

"I always told you I wasn't here to judge you. I just wanted to understand why," I said. I'd spoken to him for three hours that night, after a long flight and a frightening drive. I was exhausted and ready to leave, but I tried not to yawn or shift.

"Do you?" he asked.

"No," I said. Maybe my shoulders folded. Maybe he took pity on me.

"I ask God the same question all the time," he reassured me. "You go on and get some rest. When you figure it out, write Mr. Sam a letter and let me know."

*This article appears in the December 24, 2018, issue ofNew York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

Buy Buy Baby Robbery Downers Grove Il Car Seat Stolen

Source: https://www.thecut.com/2018/12/how-serial-killer-samuel-little-was-caught.html

0 Response to "Buy Buy Baby Robbery Downers Grove Il Car Seat Stolen"

Post a Comment